Karava of Sri Lanka

Mudaliyars

Mudaliyars

Mudaliyar is a South Indian and Tamil name for ‘first’ and a person endowed with wealth. References to the traditional Mudalis of Sri Lanka are to be found in historical literature such as the Rajavaliya, Mukkara Hatana and also Portuguese and Dutch colonial records. In feudal Sri Lanka Mudali was a military title and as such was borne only by the Kshatriya warrior caste. They were royal military officials.

The 18th century Dutch rulers appointed a few migrant Tamil Vellalas as Mudaliyars . The British who succeeded the Dutch appointed large numbers of Mudaliyars from several castes and communities in the 19th century by enlisting natives who were most likely to serve the British masters with utmost loyalty. Most of them eventually formed a caste identity called Govigama and created an interlinked family network. They called themselves Hamus and their homes Walauvas.

This class resembled English country squires, complete with large land grants from the British, residences of unprecedented scale (Referred to by the Tamil word Walauu or Walvoo) and British granted native titles - which their descendants now use as surnames. They had a uniform consisting of a Somana cloth, a long coat with decorative buttons, a sash and a short ceremonial sword called Kasthana (a corruption of 'Katana' a type of Japanese sword blade)

The De Saram Family

A De Saram family of Dutch and Malay ancestry had Sinhalised itself in the late 18th century by posing as the representatives of the masses and subsequently convincing the British rulers that they were from a Govigama caste which represented the peasant masses of the Govi caste. This was a strategic move as it gave the British rulers the impression that the De Saram family had the backing of a large body of natives. It was also the easiest route to Sinhalisation as the peasant community was widely dispersed, still unstructured and without inter-community networks or leaders.

The first notable ancestor of the De Saram family was an interpreter who accompanied the Dutch Embassy to Kandy 1731 – 1732. Despite his advanced age of 71 years, this early De Saram had to make the entire journey by foot as his social status did not warrant travel in a palanquin (JRASCB XXI 197). From there, the De Saram family progressively gained power and position by loyalty, switching religions from Dutch Protestantism to British Anglicanism and benefiting from the preference of British rulers to appoint individuals of unknown ancestry to high positions. The Govigama caste of Sri Lanka was an identity created by this family (see Govigama)

By respectively collaborating with the Dutch and British rulers, the De Sarams succeeded in marginalizing the traditional Kshatriya ruling class. The erroneous British notion of an inverted caste hierarchy in Sri Lanka is easily traceable to the documents on 'local customs' produced by this family. (See - The development and promotion of the Govi Supremacy Myth by these families).

The British naturally favored the subservient and cooperative De Saram family against the belligerent Kshatriya elite. The De Saram family was given increasing patronage and chiefly appointments and it grew in power and influence during the British period.

Governors Maitland. (1805–1811), Gordon (1883 – 1890) and others effectively used 'divide and rule' (see below) policies and created caste animosity among the native elite. In 1897 he confined all Native Headmen appointments only to the Govigama caste . A leading newspaper of the day ‘The Examiner’ stated in a letter on 30th March 1870 that the Muhandiram of Siyana Korale West was low in ability but was purely appointed for rendering domestic service for eight years to Mrs. Layard, the British Government Agent’s wife and getting good meat for her from the public market.

Right: The 4th Maha Mudliyar of British Ceylon, Christofel de Saram (assumed name Wanigasekera Ekanayake) and his son Johannes Hendrick.

Johannes was one of two de Sarams sent to England for education at the expense of the British government. He sailed to England as a 14 year old boy, on 15/03/1811, with the retiring Governor of Ceylon Maitland.

The De Saram family eventually had a strong and exclusive network of relatives as Mudaliyars by the late 19th century. Later, through marriage alliances the network extended to the Obeysekere, Dias-Bandaranaike, Ilangakoon, de Alwis, de Livera, Pieris, Siriwardena and Senanayake families. This Anglican Christian, quasi “Govigama”, network expanded further with the preponderance of native headmen appointments by the British as Mudaliyars, Korales and Vidanes from the Buddhist Govigama section of the community.

The creation of the above Mudaliyar class by the British, the production of spurious caste hierarchy lists by this group (See creation of the Govi Supremacy Myth)and changes to the land tenure system, resulted in all other Sri lankan castes being classified as low castes during this period. Particularly in the south, many large residences of departing Dutch officials were appropriated by these Mudaliyar families during the transition from Dutch to British rule.

This influential Mudaliyar class attempted to keep all other Sri Lankan castes (and even the native peasantry - the real Govi caste) out of colonial appointments. The oppression by the Mudaliars and connected headmen extended to demanding subservience, service and even restrictions on the type of personal names that could be used by other castes and even their so called 'kinsmen' from the genuine Govi caste.

The Ponnambalam-Coomaraswamy Family

As much as the De Sarams family was responsible for the rise of the Govigama caste, the Ponnambalam-Coomaraswamy Family was responsible for the 20th century, rise of the Tamil Vellala caste.

The Ponnambalam-Coomaraswamy family were the greatest beneficiaries from the efforts of Arumuga Navalar (1822 -1879) a Tamil peasant who worked tirelessly to elevate the status of the Vellalar caste in Jaffna. He banished the Karava goddess Kannaki Amman (Pattini) from temples in the North by claiming that she was a heretical Jain goddess; on the pretext of going back to tradition, he popularized officiating by Brahmin priests thereby ousting Karava priests who previously officiated at Jaffna temples; he obtained the right for Vellalars to wear the holy thread so they could pretend to be equal to the twice born Kshatriyas and Brahmins; he collaborated with Christian missionaries to obtain western education for Vellalas; he started schools for Vellalar caste students and admitted a few poor Brahmins and Chetties with them thereby too effectively raising the status of the Vellalars in the ritual hierarchy.

The ascendance of the Ponnambalam-Coomaraswamy family commences with a Coomaraswamy (1783-1836) from Point Pedro joining the seminary that Governor North started for producing interpreters. Coomaraswamy passed out and served as an interpreter from 1805. He was rewarded by the Governor with a Mudaliyar position at the age of 26 and became the Jaffna Tamil with the highest government appointment. He played a critical role as the Tamil-English interpreter when the Kandyan king Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe was captured in 1815. He was rewarded with a gold chain and medal by Governor Brownrigg in 1819 for loyal service to the British crown. (Vythilingam 36-43) There were allegations that he was not from the Vellala caste. (Jayawardena 209). James Rutnam's research has shown that Coomaraswamy's Father was Arumugampillai, a South Indian, who had migrated to Gurudavil in Jaffna. (Tribune 1957)

Right: Vellala Vellala students from Jaffna and their European teacher

Ariyaputhira, the step Father of Arunachalam Ponnambalam (1814-87) was Coomaraswamy’s brother-in-law and in 1844 Ponnambalam married Coomaraswamy’s daughter Selachchi.

Ponnambalam was appointed cashier of the Colombo Kachcheri in 1845 and deputy Coroner for Colombo in 1847. Many leading Englishmen were his friends and it transpired in the 1849 Parliamentary Commission that he used to lend money to government officials. (Vythilingam 58)

Right: Ponnanbalam Ramanathan in 1906 with his future wife Ms. Harrison (right). Several members of the family were married to western women.

His three sons P. Coomaraswamy (1849-1905), P. Ramanathan (1851-1930) and P. Arunachalam (1853-1926) were national figures and two of them, P. C. and P. A. married two daughters of Namasiyayam, an extremely successful Broker. This closely related and endogamous clan emerged as the pre-eminent Tamil family of the country and rose to national elite status. (Jayawardena 210-212)

Despite their anglicized background which propelled their rise, the family presented a staunch Hindu appearance and assumed the role of ‘Patrons of the Vellala caste'. However many of its members; Muttu Coomaraswamy, P. Coomaraswamy, P. Ramanathan and others had married western women. Ananda Coomaraswamy was married four times to western women.

They helped many young Tamils to secure employment in English Banks and Mercantile establishments. On the death of Mudaliyar Coomaraswamy’s wife in 1897, the leading daily, ‘The Ceylon Independent’ wrote “to her and her husband, almost every important Hindu family in the city owes its rise”.

The 19th century Radalas

See British Radalas for the class of ‘New Radalas’ created by 19th century British administrators in the Kandyan provinces of Sri Lanka.

The 20th century

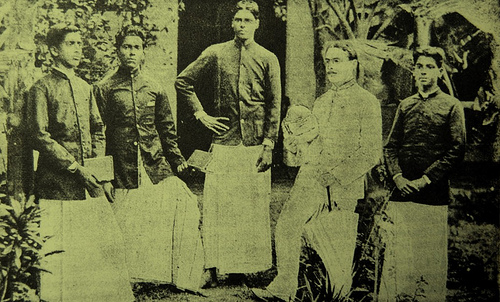

Right: Mudaliyar Don Spater Senanayake, (son of Don Bartholomew, b 1847, Arrack renter and later Plumbago merchant who learned the trade while working at the mine of Karava entrepreneur John Clovis de Silva, conferred rank of Mudaliyar by British Governor West Ridgeway) with his son-in-law F.H. Dias- Bandaranaike, sons Don Stephen (D. S. Senanayake - first Prime Minister of Ceylon), Don Charles (D.C.) and Fredrick Richard (F. R. ), daughter Maria Frances and wife Dona Catherina Elizabeth Perera. They were Anglican Christians. D. S. Senanayaka's wife Molly Dunuwila too was a Christian but the Senanayake's put on Sinhala Buddhist garb for the electorate.

The introduction of democracy in the early 20th century transferred political power to the above affiliated Senanayake, Wijewardene, Kotelawala, Jayewardene and Dias Bandaranaike families in the Southern part of the country and to interconnected Vellala families in the north. They were all from the anglicized minority of Sri Lanka and they claimed that they were from the numerous cultivator caste.

Despite their Anglican Christian background, these families were respectively accepted by the Sinhala Buddhist mass vote-base and the Tamil voters as their communal democratic leaders and representatives. Since the grant of independence by the British in 1948, Sri Lanka’s political power has rarely slipped away from this closely connected group and even so only for short periods. However, it has always been the Catholic Church and not the Anglican denomination that has been at the receiving end of the religious antipathy of the Sinhala masses. Similarly the Sinhala Buddhists of Sri Lanka are the target of Tamil hostility for the atrocities perpetrated on them by this Anglican minority.

References

- Jayawardena Kumari 2000 Nobodies to Somebodies - The Rise of the Colonial Bourgeoisie in Sri Lanka

- JRASCB The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Ceylon Branch XXI 1909 No. 62

- Peebles Patrick 1995 Social Change in Nineteenth Century Ceylon

- Vythilingam M. 1971 The life of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan Volume I

'Divide and rule' methods used by British Governors of Sri Lanka

The Caste divide

- During the last quarter of the 19th century, British Governors encouraged Inter-caste rivalry among the Sinhala speaking inhabitants of Sri Lanka to prevent the formation of anti-colonial movements. The British administrators helped loyal families of mixed origin who professed the Anglican faith of the British administrators, to merge with the numerically large Govigama middle-caste of cultivators and landlords to pose as native leaders. Among them were the De Saram family that had married Burghers, and later through other marriage alliances, created a network embracing the Obeysekere, Jayasekara, Dias-Bandaranaike, Ilangakoon, de Alwis, de Livera, Pieris and Siriwardena families. This “Govigama” Anglican Christian network expanded further with the preponderance of native headmen as Mudaliyars, Korales and Vidanes from the Buddhist Govigama section of the community. How

- Eventually the British created a very powerful class of Mudaliyars. Towards the end of the 19th century, appointments to high native positions were restricted for several years only to Anglicans from the Govigama caste. In the traditional caste hierarchy of Sri Lanka, the Govigama caste had been the 4th (or the lowest) caste. Nitinighanduwa, a spurious publication on so called native laws which was in reality designed to claim the highest status for the Govigama caste was published by the British government and it sparked the famous caste-conflict of that period. This caste antipathy remained for decades and it effectively prevented the formation of a nationalistic independence struggle in Sri Lanka. It also laid the foundation for the post-independence Govigama hegemony which has led to several youth uprisings followed by brutal mass massacres by Govigama controlled governments to suppress them. The country has been ravaged by a civil war for over two decades driven by demands for democracy and autonomy and there is brewing discontent among youth against the exploitation of the nation by a few political families.

Right: British appointed native Mudaliyars and a British official, from Tangalle in Southern Sri Lanka

The Race divide

- Through their methods of administration, divide and rule policies, census taking methods and mandatory declaration of one’s ‘Race’ on official documents, The British Governors forced the Sri Lankan population of diverse ethnic origins to become either Sinhalese or Tamil based on the language they spoke in the 19th century.

- Ethnically diverse but Sinhala speaking castes and racial groups who had their own origin myths were virtually compelled to adopt a common origin myth, the myth that all Sinhala speaking people descend from Vijaya the grandson of a lion, even though all of the Sinhalese lower-castes were originally Tamil. This myth was encouraged and popularised by the British colonials, ably aided by staunch nationalists. Prince Vijaya died without even a royal heir and subsequent royal dynasties (until the 12th century Indian born Kalinga kings) never claimed Vijayan connections. Nevertheless in the modern Sinhala psyche the ‘descent from the lion’ story has a special placeand is widely accepted unquestioningly. See lion myth & Lion flag

- Similarly in northern Sri Lanka, ethnically diverse communities of various origins but speaking Tamil, the language of trade and commerce of the region, were grouped as Malabars and subsequently relabeld as Tamils even though many of them were Malayalis and Telugus. This led to a 30 year race based civil war

Kshatriya Maha Sabha, Sri Lanka